Read the article on Timothy’s blog

here.

The global law firm DLA has overtaken Baker McKenzie to become the top grossing law firm in the world,

according to the AmLaw Daily. With a record-breaking USD $2.44 billion in top line revenue, an 8.6% increase over the prior year, DLA exceeds Baker’s USD $2.42 billion and 4.6% year over year growth. Huzzah! As reported in a breathless account on

Bloomberg Law TV, DLA accomplished this feat through savvy branding and differentiation as well as through strategic growth. But is this accomplishment meaningful to the firm’s two key stakeholder groups, namely its partners and its clients? Opinions vary.

First let’s unbundle DLA’s growth strategy. In the Bloomberg interview, Zeughauser Group consultant

Kent Zimmerman reports that “DLA was not even around 9 years ago” so becoming the top grossing law firm in such a short period is indeed an impressive feat. Problem is, that characterization is not entirely true. Or not at all true, depending on your perspective. DLA was formed by

combining multiple law firms, many of which were considered “large” in their own right and which had respectable rankings on national and international lists. The most notable of these are Piper Marbury of Baltimore, Rudnick & Wolfe of Chicago, Gray Cary & Ware of San Diego and DLA of London. Can it really be called strategic growth when 1+1=2?

To draw a bit of an odd analogy, let’s think back to our favorite ‘70s television shows. Remember when

Carol Martin and her three daughters with hair of gold joined with Mike Brady and his three boys to form the

Brady Bunch? What if Mike died in a tragic leisure suit accident and Carol sought another suitable mate. Now imagine that she married Tom Bradford, the father of eight children in

Eight is Enough. The combined brood of 14 children is no doubt impressive, but it would be a bit of a stretch to laud Carol and Tom for their strategic wisdom in achieving such a large family, at least in part because it’s not clear how the size of the family benefits anyone involved.

Growth through acquisition is no easy feat. Nonetheless, it’s a common growth strategy in corporations and law firms alike. But let’s contrast this approach with, say,

organic growth, which is

defined as growth by increasing output and enhancing sales, and excluding profits or growth from takeovers, acquisitions or mergers. A highly visible example of impressive organic growth is

Apple Computer, which had USD $9.8 billion in revenues in 1996 when Steve Jobs returned to lead the struggling company he had co-founded, and which in 2012 generated USD $157 billion in revenues. Pop quiz: name two or three acquisitions Apple has made that materially increased its overall revenue. Too hard? Then name just one. Still can’t do it? Simply put, Apple has

innovated its way to success, eschewing the

strategy of buying of revenue streams, profitable or otherwise, in lieu of launching new products that the market is eager to purchase.

DLA, as we’ve observed, in part combined its way to success. But there’s more. Turning back to the Bloomberg interview once again, Zimmerman reports that DLA used its growing wealth to “acquire talent with large books of business.” Said another way, DLA recruited lawyers with established and portable clients, and paid these lawyers handsomely to bring their clients and client revenues to the firm. Again, nothing wrong with this, but can it really be called strategic growth when 1+1+1=3?

What about DLA’s purported investment in branding and differentiation? According to

Acritas, a UK-based consulting firm that provides market research and benchmarking services for top law firms,

DLA now ranks in the top 5 among US law firm brands. It appears the survey methodology relies on “unaided response” – the questions are not multiple choice and the respondent is not prompted – and a high number of unaided responses is generally a good indicator of solid brand strength, though there are certainly more

statistically rigorous methodologies. Let’s turn to

Dr. Ann Lee Gibson, trained statistician and advisor to law firms on competitive intelligence and business development, for a bit more context:

“Generally speaking, the larger the firm, the more likely it is that members of your sample will have worked with that firm and will offer its name. Large firms also spin off more in-house counsel and may receive more votes because of their alma mater primacy and status. It’s also likely that recently newsworthy or notorious firms will come to mind compared to firms not currently in the headlines. “Which firms come to mind?” may produce lists that may have, metaphorically speaking, Miley Cyrus ranking higher than Meryl Streep or Anne Hathaway. It will produce lists that, un-metaphorically speaking, rank Fulbright higher than Wachtell and rank Foley Lardner higher than Davis Polk.”

Does anyone recall that DLA generated a

lot of headlines a few months ago? Does anyone recall

why? Does it matter? When several hundred general counsel are asked which law firms come to mind, it’s no surprise that DLA ranks highly.

But let’s get right to the heart of the matter: is the distinction as the top grossing law firm good for partners and good for clients? To address the partners’ perspective, let’s turn to

Patrick Fuller, an executive at legal technology provider

Content Pilot and previously a management consultant:

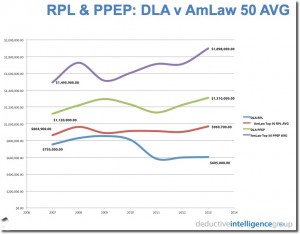

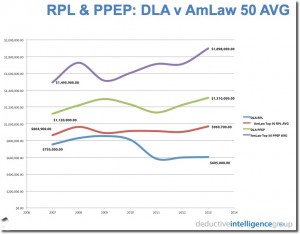

“The best way to analyze the financial implications for DLA’s partners is to compare its results to the market. Has the growth in size and revenue generated greater profits for the shareholders? Looking back to 2007, DLA generated revenue of just over USD $1 billion, with revenue per lawyer (RPL) of $0.8 million and profits per equity partner (PPeP) of $1.1 million. In 2013, overall revenue is $2.4 billion, with RPL at $0.6 million and PPeP at $1.3 million.

This represents a CAGR (compound annual growth rate) of 15.8% on overall revenue, -3.6% on RPL and 2.65% on PPeP. Contrast this with the overall AmLaw 50 growth of 4% on overall revenue, 1.9% on RPL and 4.1% on PPeP.

In case your head hurts from so much math, the punch line is this: Despite enormous growth in revenues, DLA’s profit growth has lagged the market, and in real dollars the equity partners take home, on average, only marginally more than they did before this tremendous growth spurt. For example, the PPeP for DLA has increased 17% since 2007, while the average AmLaw 50 PPeP has increased 27% over the same period. Additionally, the RPL for DLA has decreased nearly 20% since 2007, while over the same period, the average AmLaw 50 firm RPL increased 12%. If one objective of growth through acquisition is to improve financial performance, then growing the numerator and the denominator in roughly equal proportion isn’t particularly effective. Note that Baker & McKenzie grew profits in the last year by an astounding 9.1% even as it “slipped” to #2 in gross revenue, suggesting that its leaders’ focus isn’t on growing top line revenue, but growing profits. As Kent Zimmerman reports in the Bloomberg Law interview, Baker accomplished this in large part by focusing on key clients.”

During my tenure as a corporate executive, my teams and I identified numerous acquisition targets and we were also approached regularly by suitors looking to sell their businesses to us. In one role, my division was extraordinarily profitable – far more than our corporate peers, and far more than even the healthy profit margins enjoyed by large law firms. As a result, practically any investment we made was dilutive, meaning that if we spent $1 and it didn’t immediately return the usual margin we enjoyed in our base business, our profit margin declined. As you might imagine, our corporate parent wasn’t fond of profit dilution so the bar was pretty high for us – we couldn’t just add revenue streams, and we couldn’t just add profitable revenue streams. We could only add profitable revenue streams that maintained our current margins. Said another way, for us 1+1+1 must equal 6. Or 8. So we didn’t pull the trigger on too many acquisitions.

In the corporate space growing profit through acquisitions can best be achieved by exploiting synergies. As I’ve discussed

elsewhere, law firm leaders tend to view mergers as an overall growth engine when in fact most result solely in

revenue growth. Profits don’t typically grow substantially after a merger because there are few synergies to exploit when you smash together two organizations, each with large compensation, benefits, real estate and overhead expenses. Sure, you can eliminate a few redundant staff positions and maybe combine some technology, but these aren’t strategic synergies so much as minor operational savings.

For a law firm to generate

strategic synergy, we have to turn to the other key law firm stakeholders, the clients. As Patrick states above, Baker grew its profit margins. Could this mean it raised its rates while holding the line on expenses? Possibly, though Zimmerman highlights the firm’s focus on key clients as a catalyst, and we have every reason to believe this is true. The math supporting

key client programs is simple and effective, particularly because it benefits both clients and partners. Let’s drill into just two factors:

penetration and

retention.

Penetration is how I refer to the impact of a law firm’s cross-selling efforts. A client with high penetration has retained the law firm for multiple matters across a variety of practices in a variety of locations, and there are likely many lawyer-client relationships at all levels. This reflects a positive match between the client’s needs and the law firm’s ability to understand and address these needs; perhaps it reflects a broad overlap between the firm’s expertise and the client’s business challenges; it possibly reflects a similar geographic footprint. Without question, a client that becomes so embedded into a firm is a

firm client, not an individual rainmaker’s client, and as such the firm can treat the relationship with a long-term view rather than maximizing hours on a short-term basis to satisfy a hungry rainmaker who might leave at any minute. It’s nearly impossible to achieve high penetration without an organized client team approach, and this requires aligned incentives that go well beyond paying for origination or high billable hours.

Retention refers to the rate at which clients purchase services again and again from a law firm. Much like penetration, a high retention rate results from deep relationships and a sense of shared purpose. Of late, long-term relationships have suffered when partners adjust leverage to maintain high billable hours and delegate less to associates, or when billing rates are increased to make up for lower utilization elsewhere. Clients also factor in predictability, the use of alternative fee arrangements, project management capabilities and other “service” components when creating a

quality index. Clearly, achieving the desired legal outcome is no longer enough. Law firms that focus on retention rate adjust compensation schemes to reward behavior that provides long-term benefits to the firm.

There are other factors as well, but the key takeaway is that high penetration and high retention reduce the firm’s cost to acquire the next engagement (most firms spend a fortune pursuing new clients and relatively little delighting existing clients). This focus also allows the firm to incorporate process improvements and

project management to drive efficiencies – a must-have in a world where clients increasingly pay less for routine work. And internally, of course, having stickier clients reduces the firm’s reliance on overpaying for lateral recruits with huge books of business to replace revenues lost from defecting rainmakers. This is just a glimpse into the math supporting strategic synergy. But there is much more.

I have no particular opposition to mergers and acquisitions as a growth strategy. And I have no particular opposition to rankings. I do, however, believe that equating revenue growth as a de facto demonstration of “success” — particularly when that growth stems primarily from business combinations — is a bit of a stretch. While the combined

Brady Bunch and

Eight is Enough family yields sufficient children to field both a baseball team and a basketball team, this is not the same as declaring both teams to be league champions. That distinction is yet to be earned.

Update: Here are a few additional thoughts to address a number of offline questions. I don’t think most law firm growth stems from ego, or, said another way, from law firm leaders beating their chests and playing one-upmanship with their competitors. I believe most growth stems from either a financial objective or an income-smoothing objective. I’ve addressed the former point above — growing revenue is not the same as growing profit and may generate mixed results — but to the latter point, sustainability across business cycles is a perennial challenge for

any business. Income smoothing, or the desire to maintain a steady profit stream despite uncertain and variable economic conditions, drives organizations to diversify. The goal is to have one practice group that excels during one business cycle, say M&A during a period of low borrowing rates, favorable tax treatment, and a hassle-free regulatory environment, and another practice group that excels in a counter-cyclical time, say bankruptcy or securities litigation during a period of tight credit and increased regulatory scrutiny. When one is up, the other is down; when one is down, the other is up. This approach compels firms to not only build or acquire practices in diverse practices, but across geographies as well, since emerging markets and established economies often operate simultaneously under different business cycles.

A regular topic of debate in business academia is whether an individual

company is the right vehicle for

portfolio diversification, allowing an investor to buy one security and maintain steady growth despite troubling economic conditions in one or more of the company’s markets, or whether an investor is better off diversifying on his own, buying securities of different, narrowly-focused, companies in such a fashion as to maximize each company’s performance at the peak of its business cycle. In the legal marketplace, the question is whether a firm is better off focusing intensely on one or two practices that are “hot” and riding the wave and generating maximum profits until the practice dies or is commoditized, and then reinvent itself and find a new focus, or even disband, or whether the partners are better off diversifying across practices so the firm is always generating modest profits. It’s a simple risk/reward equation. The question for law firm leaders must be

“Does our practice mix and global platform provide a specific and unique benefit that compels our client base to engage our one-stop-shop services?”

Too often firm leaders stop at the feature, not the benefit, or, in other words, many believe it’s self-explanatory that clients will benefit from a diverse practice footprint. Clients, on the other hand, often lament that a global law firm has few notable synergies: business knowledge acquired in one practice or in one office is rarely translated to help other firm lawyers get up to speed, so there’s a constant learning curve; most firms have a differential service posture, which often stems from allowing the partners to practice law as they see fit rather than standardize how clients interact with the firm; and many firms present all practices as equally capable when in fact some are world-leading and some are merely mediocre, leaving the client to deduce what services are actually premium in nature. Global clients are often quite capable of hiring multiple niche provider law firms across geographies to suit their unique needs, so a law firm seeking a global footprint had better know, and be able to clearly articulate, explicitly how its particular mix offers an advantage to the client. Otherwise, the global law firm is really just a big collection of silo practices sharing a logo and letterhead, as well as sharing diluted earnings.

Tags: Law Firm, Law Firm Management

During my tenure as a corporate executive, my teams and I identified numerous acquisition targets and we were also approached regularly by suitors looking to sell their businesses to us. In one role, my division was extraordinarily profitable – far more than our corporate peers, and far more than even the healthy profit margins enjoyed by large law firms. As a result, practically any investment we made was dilutive, meaning that if we spent $1 and it didn’t immediately return the usual margin we enjoyed in our base business, our profit margin declined. As you might imagine, our corporate parent wasn’t fond of profit dilution so the bar was pretty high for us – we couldn’t just add revenue streams, and we couldn’t just add profitable revenue streams. We could only add profitable revenue streams that maintained our current margins. Said another way, for us 1+1+1 must equal 6. Or 8. So we didn’t pull the trigger on too many acquisitions.

In the corporate space growing profit through acquisitions can best be achieved by exploiting synergies. As I’ve discussed elsewhere, law firm leaders tend to view mergers as an overall growth engine when in fact most result solely in revenue growth. Profits don’t typically grow substantially after a merger because there are few synergies to exploit when you smash together two organizations, each with large compensation, benefits, real estate and overhead expenses. Sure, you can eliminate a few redundant staff positions and maybe combine some technology, but these aren’t strategic synergies so much as minor operational savings.

For a law firm to generate strategic synergy, we have to turn to the other key law firm stakeholders, the clients. As Patrick states above, Baker grew its profit margins. Could this mean it raised its rates while holding the line on expenses? Possibly, though Zimmerman highlights the firm’s focus on key clients as a catalyst, and we have every reason to believe this is true. The math supporting key client programs is simple and effective, particularly because it benefits both clients and partners. Let’s drill into just two factors: penetration andretention.

Penetration is how I refer to the impact of a law firm’s cross-selling efforts. A client with high penetration has retained the law firm for multiple matters across a variety of practices in a variety of locations, and there are likely many lawyer-client relationships at all levels. This reflects a positive match between the client’s needs and the law firm’s ability to understand and address these needs; perhaps it reflects a broad overlap between the firm’s expertise and the client’s business challenges; it possibly reflects a similar geographic footprint. Without question, a client that becomes so embedded into a firm is a firm client, not an individual rainmaker’s client, and as such the firm can treat the relationship with a long-term view rather than maximizing hours on a short-term basis to satisfy a hungry rainmaker who might leave at any minute. It’s nearly impossible to achieve high penetration without an organized client team approach, and this requires aligned incentives that go well beyond paying for origination or high billable hours.

Retention refers to the rate at which clients purchase services again and again from a law firm. Much like penetration, a high retention rate results from deep relationships and a sense of shared purpose. Of late, long-term relationships have suffered when partners adjust leverage to maintain high billable hours and delegate less to associates, or when billing rates are increased to make up for lower utilization elsewhere. Clients also factor in predictability, the use of alternative fee arrangements, project management capabilities and other “service” components when creating a quality index. Clearly, achieving the desired legal outcome is no longer enough. Law firms that focus on retention rate adjust compensation schemes to reward behavior that provides long-term benefits to the firm.

There are other factors as well, but the key takeaway is that high penetration and high retention reduce the firm’s cost to acquire the next engagement (most firms spend a fortune pursuing new clients and relatively little delighting existing clients). This focus also allows the firm to incorporate process improvements and project management to drive efficiencies – a must-have in a world where clients increasingly pay less for routine work. And internally, of course, having stickier clients reduces the firm’s reliance on overpaying for lateral recruits with huge books of business to replace revenues lost from defecting rainmakers. This is just a glimpse into the math supporting strategic synergy. But there is much more.

I have no particular opposition to mergers and acquisitions as a growth strategy. And I have no particular opposition to rankings. I do, however, believe that equating revenue growth as a de facto demonstration of “success” — particularly when that growth stems primarily from business combinations — is a bit of a stretch. While the combined Brady Bunch and Eight is Enough family yields sufficient children to field both a baseball team and a basketball team, this is not the same as declaring both teams to be league champions. That distinction is yet to be earned.

Update: Here are a few additional thoughts to address a number of offline questions. I don’t think most law firm growth stems from ego, or, said another way, from law firm leaders beating their chests and playing one-upmanship with their competitors. I believe most growth stems from either a financial objective or an income-smoothing objective. I’ve addressed the former point above — growing revenue is not the same as growing profit and may generate mixed results — but to the latter point, sustainability across business cycles is a perennial challenge for any business. Income smoothing, or the desire to maintain a steady profit stream despite uncertain and variable economic conditions, drives organizations to diversify. The goal is to have one practice group that excels during one business cycle, say M&A during a period of low borrowing rates, favorable tax treatment, and a hassle-free regulatory environment, and another practice group that excels in a counter-cyclical time, say bankruptcy or securities litigation during a period of tight credit and increased regulatory scrutiny. When one is up, the other is down; when one is down, the other is up. This approach compels firms to not only build or acquire practices in diverse practices, but across geographies as well, since emerging markets and established economies often operate simultaneously under different business cycles.

A regular topic of debate in business academia is whether an individual company is the right vehicle for portfolio diversification, allowing an investor to buy one security and maintain steady growth despite troubling economic conditions in one or more of the company’s markets, or whether an investor is better off diversifying on his own, buying securities of different, narrowly-focused, companies in such a fashion as to maximize each company’s performance at the peak of its business cycle. In the legal marketplace, the question is whether a firm is better off focusing intensely on one or two practices that are “hot” and riding the wave and generating maximum profits until the practice dies or is commoditized, and then reinvent itself and find a new focus, or even disband, or whether the partners are better off diversifying across practices so the firm is always generating modest profits. It’s a simple risk/reward equation. The question for law firm leaders must be “Does our practice mix and global platform provide a specific and unique benefit that compels our client base to engage our one-stop-shop services?”

Too often firm leaders stop at the feature, not the benefit, or, in other words, many believe it’s self-explanatory that clients will benefit from a diverse practice footprint. Clients, on the other hand, often lament that a global law firm has few notable synergies: business knowledge acquired in one practice or in one office is rarely translated to help other firm lawyers get up to speed, so there’s a constant learning curve; most firms have a differential service posture, which often stems from allowing the partners to practice law as they see fit rather than standardize how clients interact with the firm; and many firms present all practices as equally capable when in fact some are world-leading and some are merely mediocre, leaving the client to deduce what services are actually premium in nature. Global clients are often quite capable of hiring multiple niche provider law firms across geographies to suit their unique needs, so a law firm seeking a global footprint had better know, and be able to clearly articulate, explicitly how its particular mix offers an advantage to the client. Otherwise, the global law firm is really just a big collection of silo practices sharing a logo and letterhead, as well as sharing diluted earnings.

During my tenure as a corporate executive, my teams and I identified numerous acquisition targets and we were also approached regularly by suitors looking to sell their businesses to us. In one role, my division was extraordinarily profitable – far more than our corporate peers, and far more than even the healthy profit margins enjoyed by large law firms. As a result, practically any investment we made was dilutive, meaning that if we spent $1 and it didn’t immediately return the usual margin we enjoyed in our base business, our profit margin declined. As you might imagine, our corporate parent wasn’t fond of profit dilution so the bar was pretty high for us – we couldn’t just add revenue streams, and we couldn’t just add profitable revenue streams. We could only add profitable revenue streams that maintained our current margins. Said another way, for us 1+1+1 must equal 6. Or 8. So we didn’t pull the trigger on too many acquisitions.

In the corporate space growing profit through acquisitions can best be achieved by exploiting synergies. As I’ve discussed elsewhere, law firm leaders tend to view mergers as an overall growth engine when in fact most result solely in revenue growth. Profits don’t typically grow substantially after a merger because there are few synergies to exploit when you smash together two organizations, each with large compensation, benefits, real estate and overhead expenses. Sure, you can eliminate a few redundant staff positions and maybe combine some technology, but these aren’t strategic synergies so much as minor operational savings.

For a law firm to generate strategic synergy, we have to turn to the other key law firm stakeholders, the clients. As Patrick states above, Baker grew its profit margins. Could this mean it raised its rates while holding the line on expenses? Possibly, though Zimmerman highlights the firm’s focus on key clients as a catalyst, and we have every reason to believe this is true. The math supporting key client programs is simple and effective, particularly because it benefits both clients and partners. Let’s drill into just two factors: penetration andretention.

Penetration is how I refer to the impact of a law firm’s cross-selling efforts. A client with high penetration has retained the law firm for multiple matters across a variety of practices in a variety of locations, and there are likely many lawyer-client relationships at all levels. This reflects a positive match between the client’s needs and the law firm’s ability to understand and address these needs; perhaps it reflects a broad overlap between the firm’s expertise and the client’s business challenges; it possibly reflects a similar geographic footprint. Without question, a client that becomes so embedded into a firm is a firm client, not an individual rainmaker’s client, and as such the firm can treat the relationship with a long-term view rather than maximizing hours on a short-term basis to satisfy a hungry rainmaker who might leave at any minute. It’s nearly impossible to achieve high penetration without an organized client team approach, and this requires aligned incentives that go well beyond paying for origination or high billable hours.

Retention refers to the rate at which clients purchase services again and again from a law firm. Much like penetration, a high retention rate results from deep relationships and a sense of shared purpose. Of late, long-term relationships have suffered when partners adjust leverage to maintain high billable hours and delegate less to associates, or when billing rates are increased to make up for lower utilization elsewhere. Clients also factor in predictability, the use of alternative fee arrangements, project management capabilities and other “service” components when creating a quality index. Clearly, achieving the desired legal outcome is no longer enough. Law firms that focus on retention rate adjust compensation schemes to reward behavior that provides long-term benefits to the firm.

There are other factors as well, but the key takeaway is that high penetration and high retention reduce the firm’s cost to acquire the next engagement (most firms spend a fortune pursuing new clients and relatively little delighting existing clients). This focus also allows the firm to incorporate process improvements and project management to drive efficiencies – a must-have in a world where clients increasingly pay less for routine work. And internally, of course, having stickier clients reduces the firm’s reliance on overpaying for lateral recruits with huge books of business to replace revenues lost from defecting rainmakers. This is just a glimpse into the math supporting strategic synergy. But there is much more.

I have no particular opposition to mergers and acquisitions as a growth strategy. And I have no particular opposition to rankings. I do, however, believe that equating revenue growth as a de facto demonstration of “success” — particularly when that growth stems primarily from business combinations — is a bit of a stretch. While the combined Brady Bunch and Eight is Enough family yields sufficient children to field both a baseball team and a basketball team, this is not the same as declaring both teams to be league champions. That distinction is yet to be earned.

Update: Here are a few additional thoughts to address a number of offline questions. I don’t think most law firm growth stems from ego, or, said another way, from law firm leaders beating their chests and playing one-upmanship with their competitors. I believe most growth stems from either a financial objective or an income-smoothing objective. I’ve addressed the former point above — growing revenue is not the same as growing profit and may generate mixed results — but to the latter point, sustainability across business cycles is a perennial challenge for any business. Income smoothing, or the desire to maintain a steady profit stream despite uncertain and variable economic conditions, drives organizations to diversify. The goal is to have one practice group that excels during one business cycle, say M&A during a period of low borrowing rates, favorable tax treatment, and a hassle-free regulatory environment, and another practice group that excels in a counter-cyclical time, say bankruptcy or securities litigation during a period of tight credit and increased regulatory scrutiny. When one is up, the other is down; when one is down, the other is up. This approach compels firms to not only build or acquire practices in diverse practices, but across geographies as well, since emerging markets and established economies often operate simultaneously under different business cycles.

A regular topic of debate in business academia is whether an individual company is the right vehicle for portfolio diversification, allowing an investor to buy one security and maintain steady growth despite troubling economic conditions in one or more of the company’s markets, or whether an investor is better off diversifying on his own, buying securities of different, narrowly-focused, companies in such a fashion as to maximize each company’s performance at the peak of its business cycle. In the legal marketplace, the question is whether a firm is better off focusing intensely on one or two practices that are “hot” and riding the wave and generating maximum profits until the practice dies or is commoditized, and then reinvent itself and find a new focus, or even disband, or whether the partners are better off diversifying across practices so the firm is always generating modest profits. It’s a simple risk/reward equation. The question for law firm leaders must be “Does our practice mix and global platform provide a specific and unique benefit that compels our client base to engage our one-stop-shop services?”

Too often firm leaders stop at the feature, not the benefit, or, in other words, many believe it’s self-explanatory that clients will benefit from a diverse practice footprint. Clients, on the other hand, often lament that a global law firm has few notable synergies: business knowledge acquired in one practice or in one office is rarely translated to help other firm lawyers get up to speed, so there’s a constant learning curve; most firms have a differential service posture, which often stems from allowing the partners to practice law as they see fit rather than standardize how clients interact with the firm; and many firms present all practices as equally capable when in fact some are world-leading and some are merely mediocre, leaving the client to deduce what services are actually premium in nature. Global clients are often quite capable of hiring multiple niche provider law firms across geographies to suit their unique needs, so a law firm seeking a global footprint had better know, and be able to clearly articulate, explicitly how its particular mix offers an advantage to the client. Otherwise, the global law firm is really just a big collection of silo practices sharing a logo and letterhead, as well as sharing diluted earnings.